Peripatetic Curmudgeon

Read Posts in Chronological Order

Wednesday, July 25, 2012

Amsterdam--Hidden Mennonite Church

Amsterdam—July 25, cont. The Hidden Mennonite Church

So, Adriaan Plak walks us to the “hidden church.” We go

across the canal and west a little ways from the University Library. We

approach a door that is plain . . . it does not stand out from any other door

on this street-front building. In fact, that is why it is called a “hidden

church”—meaning it is not recognizable from the street.

We walk inside and can see immediately that we are in a

large facility with a very church-like feel. (There is the secretary’s office,

the coffee machine, and stacks of bulletins, brochures, and other church

paraphernalia.) We walk around to the sanctuary. It is pretty plain: dark

wooden floors and pulpit, large balcony with painted posts and railings. A very

interesting art piece is on the pulpit. You’ll see a picture of it. There are a

couple of nice chandeliers—the only decorative pieces.

The center of the sanctuary has folding chairs. In the old

days they were stacked in the foyer before the service began. Each female churchgoer

took a chair after paying a five-cent piece and carried it somewhere into the

middle area. The surrounding benches were intended for the men. The children

from the orphanage that the church operated and paupers usually sat in the

gallery.

In walked a slight, younger middle-aged guy who introduces

himself as Marcel Alblas. Adriaan excuses himself and Marcel takes over. He is

engaging, obviously loves to talk (and talk about his church--he is the

facility manager and guest host) and has a wonderful if understated sense of

humor.

Marcel says he grew up in the “Bible Belt”—the one in

Holland— which means it was “Reformed” (his words.) It was very conservative:

no cinema or swimming on Sundays. That strictness was too much for his family

and pushed them toward a more liberal outlook.

He is definitely what you might call a “liberal” (you might pick up on

that in some of what he said; see below)

He took us on a tour of the church and unloaded more about

the history and practices of Mennonites in Amsterdam than we could possibly

absorb. (I took notes as fast as I could.) It was an enjoyable conversation and

fascinating. Once again, it was almost too much to believe—discovering this

church, being here and hearing all of this was nowhere near my mind a few short

hours ago.

Here is short summary of his comments:

In the earliest days, from 1530, during the times of

persecution and weirdness (he mentioned the “naked

truthers”), Mennonites met

in private homes. At the beginning of the 17th century, when the

Protestants began to tolerate the Mennonites to a certain degree, they began to

meet more often in central gathering places. Still, they did not publicize to a

great degree the locations of these places.

The Mennonites were allowed to have a meeting place but they

could not be visible from the street, could have no clock tower, and no church

name. Marcel commented that the city fathers managed the churches like they

managed the drugs and prostitution: tolerate them but know where they are so

you can keep an eye on them (thus the “coffee shops”, the Red Light

District—and hidden but registered churches.)

In 1607, the first building was built on this site. This

meeting place was called “Near the Lamb.” One might think this was a use of the

biblical reference to Christ the Lamb. Actually it referred to a lamb on the

gable of the nearby brewery. The lamb is still the church’s logo.

In 1639, a larger structure was built on and in 1839, the

roof took its present shape. Over the years, the complex continued to grow. It

was used for meetings, a library, and Bible classes. This is a large facility.

It is the headquarters of the General Mennonite Society and the Mennonite

Centre for Congregational Building. Marcel refers to it as “the Vatican of

Mennonites.”

A library was founded in 1680 with a pastor’s small

collection, to be used for the benefit of preachers. This collection expanded

throughout the 18th and 19th centuries through many

endowments and has grown into a collection of books by and about Mennonites unequalled

in the world. Guess where it is . . . it is “on loan” to the University of

Amsterdam across the canal.

There is another library used by the Mennonite Seminary

(which uses space in this church also). This library contains literature in the

field of church history, doctrine, biblical studies, and ethics.

He showed us a large multi-purpose room. This is where the

Church Board meets. This is also the room where they feed the homeless on

Friday nights. It is also the room where they welcomed the Queen a couple of

years ago.

“Mennonites have a strong belief in strict separation of

church and state,” he said. “We have a hard time voting for so-called

‘Christian political parties.’ They sometimes take hard stands on issues they

claim are ‘Christian’ but these are positions with which you or I or some other

Christian may not agree. Sometimes they do not act like Christians at all. Best

leave politics to politicians and faith to believers and the church. We can

sort things out.”

“The Netherlands is not a Christian nation but it has

Christian values. That is why the state

takes care of the elderly and homeless. That is also why we do not send our

children to the state-funded religious schools but to the public schools,

instead.”

The pastor is not called “pastor”. He is called a “teacher”

(leeraren)—which is what his role is

in the church body. The pastor is just one person in the congregation—he is not

“higher” than anyone else. Actually the congregation is the ruling body. The

pastor gets one hour a week. At the beginning of the worship service, the

president of the congregation shakes his hand and introduces him. At the end of

the hour, the president comes up, shakes his hand and sends him back to his

seat.

During Reformation time, this was the biggest church in

Amsterdam, Marcel said. Today, it is the smallest. It has consistently grown

smaller. I asked him the same question I asked Adriaan: “Will this church be

here in a hundred years?” “Of course it will,” he replied. “Because the spirit

is still alive in people who seek truth and who wish to be free. We don’t have

all the truth but we are near it. We are always seeking it.”

Mennonites believe strongly that faith is demonstrated in

deeds. For Marcel (and apparently this church), that means several things. It

means they feed the poor and have children’s ministries. They are also

gay-friendly—open and accepting. Next month they will host a gay wedding. (This

is actually not a big issue in Amsterdam, as you may know. Homosexuality is

very public and openly accepted. Amsterdam Gay Pride is socially and

politically active. The “Gay Monument” is not far from this church. The big,

pink, balloon barge is hard to miss in the annual Canal Parade. I saw a picture

. . . .)

They believe that every person is responsible for “writing

his own creed.” That is, each person defines his own understanding of and

experience with God and is responsible for how he expresses that faith. “We

don’t dictate how others should believe. People are not expected to check their

mind at the door (for example, evolution is not even an issue; science and

religion walk hand in hand),” he said.

“Attendance is not expected every Sunday of every church

member. It is just as important that members live the faith. They should

occasionally use a Sunday to do some kind of service. Then they come to church

to be recharged.”

This church sponsors a public forum on social issues each

month. They bring in speakers from the community who speak and lead discussions

on a wide range of topics. Apparently this has become quite a popular event.

Other churches around Holland are copying the model. Marcel was very proud that

one of the speakers coming soon is an outspoken atheist who will lead a

discussion on why she rejects faith in God altogether. The name of this event

is called in Dutch, “Dopers Café.” It roughly translates “The Baptist Café” but

its English appearance has a different connotation.

Mennonites may be progressive here in the big city but they

have not forgotten from whence they came. Marcel brought out a big,

leather-bound book, a quite old one by the looks of it. We could not find a

publication date in it. He said they put this book on the altar every Sunday

morning. When he first saw it, he was put off. “What is this?” he asked. “Are

they worshiping this book instead of God?” Then he learned why the book is made

public on a regular basis. It is put out every week to remind the people of

their heritage and of the people who’s faith cost them their lives. It is an

antique copy of The Martyr’s Mirror.

So, we have now seen the spectrum—there are very

conservative Mennonites with the traditional dress and lifestyle; the more

“moderate” (as we met in Langnau); and today we meet the urban liberal. Each

church has adapted its faith and practice to its surroundings. Somehow, though

I think he would respect his Dutch brother, Hans Jützi down in the Emmental

might not agree with some of the social positions and biblical interpretations

of Marcel Alblas up in Amsterdam. Marcel might think that the country version

of Mennonites is a bit restrained—but he would insist that every believer must

“write his own creed.”

Here is the illustration of the fact that the movement

grounded in “evangelical humanism”, rigorous biblical study, and insistence on

freedom to live one’s faith as conscience dictates and the Spirit leads is

capable of manifesting itself in a stark array of disparate expressions.

Oh yes, one other thing: when I mentioned to Marcel that I

was from the “Baptist” tradition in the United States, he said, “Oh, you are

part of the English!” I wasn’t sure just what he meant. He led us to a large

display on the long entrance wall and showed us a schematic description that

portrayed the history of this Amsterdam Anabaptist congregation. Refugees from

across Europe had come together in this church. There were Flemish, Frisian,

other European groups . . . and an English group. The names of all the deacons

and preachers (“teachers”) of the congregation from the very beginning up to

present were there.

And there, right

there in the middle of the display, up at the top, under the column heading

“English”, dated 1608, was the name: “John Smyth.”

So, this is the place. This is the place for which I have

been looking. This is where those English “Baptists” and those Dutch Mennonites

came together, worshiped, studied, discussed, argued and prayed. It was from

here that the little English group eventually went back to England and then to

the New World, taking with them some portion of the legacy of faithful European

Anabaptists.

I guess I got my answer . . . today . . . the last day of

the journey.

Oh, yes. After this amazing day, we finally made it to the Old Church. There are some photos below.

And, I dropped by "Our Lord in the Attic". They had my notebook.

Oh, yes. After this amazing day, we finally made it to the Old Church. There are some photos below.

And, I dropped by "Our Lord in the Attic". They had my notebook.

Walking along the canal towards the "hidden" church. Actually, you would never know there is a quite large church facility behind the black door with the arched top, in the center of the picture. The Catholic Church next door is much more obvious!

The front door of the "hidden" church.

This is the sign that hangs over the door. "Mennonite Community" (or "Fellowship")

The Lamb symbol is taken from the "Lamb Brewery"which was nearby.

A metal plaque on the exterior wall above the door shows a lamb (to symbolize this church) and a sun and a tower which are the symbols of two nearby "hidden" churches. The plaque reveals that they knew about and cooperated with each other.

“A book lies open on the pulpit. Pages flutter as if playfully caught up by the wind to be suspended frozen in the air.” This is the poetic description of a sculpture by a local artist on exhibit this summer in the church. The sculpture is done in alabaster.

Marcel gently holds the church's old copy of The Martyr's Mirror.

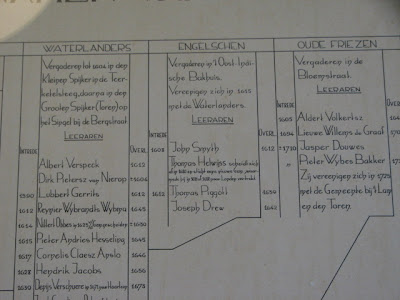

The wall display which shows the history of this church. It names all the deacons and pastors (teachers) who have served in this church from its beginning. Each column represents Mennonites from various regions who came together.

In the middle of the display is the "English" column. Two very familiar names, John Smyth and Thomas Helwys, are right at the top. Note that they are listed as "leeraren" or teachers of the church in 1608.

This sign beside the door next to the church door indicates this is the meeting place for the Mennonite Seminary and the General Mennonite Society.

After we left the hidden church, we walked down to the Old Church. Here are a few photos.

A brief history of the Old Church in Amsterdam.

Note the rather dismal tone, both in terms of how the Protestants treated the formerly Catholic cathedral as well as how the "new church" eventually replaced.

A confessional booth in the Old Church. This would have made a perfect wardrobe for a C. S. Lewis play.

The Old Church has a floor of grave stones and a wooden ceiling.

The organ of the Old Church. It is interesting to note that these very nice appointments are maintained in a church that is rarely used a church anymore.

This is the grave of Rembrandt's wife.

Every church has a first song and a last song in its worship service. These hymn boards were in every church we have seen.

The dark, somber pulpit has a highly polished brass railing.

When we build a balcony or a loft for our sound booth, we can use a spiral staircase like this one.

Amsterdam--The Holy Grail (sort of)

Amsterdam—July 25

The Holy Grail (sort of)

I have a confession: I came here to Amsterdam not certain we

would find much to add to our Anabaptist journey. I had scarcely done any

research—it had not yielded anything to which I could relate. Besides, where

does one even start to look in such a big, sprawling city?

Today is our last day in Amsterdam. Tonight we fly back to

Zurich and then home. We have only odds and ends on our agenda today: go back

to the Old Church and check it out; then maybe go by “Our Lord in the Attic” on

the remote chance my notebook is there. Not too exciting, really.

Do not misunderstand: the past three days have been great.

Amsterdam is a fascinating place to visit. Our experiences here have provided

some great stories and prompted important thinking. But this is it. No dramatic

conclusions—just pack up and go home

My suspicion proved accurate: I don’t really have anything

from the past several days that added substantively to my study project. That

leaves me with a bit of an empty feeling, maybe even a tiny touch of

guilt: I should have looked harder; I

should be doing something more; there should be a good way to wrap this up. I

began the day with these feelings but no idea of how to get a grip on them.

First, a little back

story: when we were in Langnau, weeks ago, I did an Internet search one

evening looking for information on Menno Simons (knowing that we would be

coming this direction near the end of our trip.) I came across the webpage of a

“Menno Simons Center”. The information as to its “what and where” was vague so

I emailed the director of the Center who was listed on the website.

Surprisingly, he emailed back almost immediately and told me

the Center was “virtual”; i.e., entirely on-line—there is no “place” to visit.

He mentioned, however, that there was a very large collection of Mennonite

writings at the University of Amsterdam and that perhaps I should arrange a

visit there when in the city. He said the “professor of Anabaptist studies”

(who knew there was such a person?!) at the university was on holiday but I

might be able to find the curator of the collection, a certain Adriaan Plak.

I essentially dismissed the idea—it is summer, the

university is going to be closed and quiet, people will be hard to find, I probably

could not get access, I can’t read Dutch. Very likely, the University itself

will be hard to locate. (In these ancient cities, the universities typically do

not have a central campus—the buildings are scattered all over the place.) The

suggestion went into the “good idea but highly unlikely” file. I jotted down

the information on the only piece of paper I had at the moment, a corner of a

used napkin, and stuck it in my wallet. Then, I basically forgot about it.

Now, back to today.

We start our trek to the Old Church. We decided to go a different route and

take some back streets, going where we had not gone before. We were uncertain

as to exactly where we would come out but it would be fun to explore.

Well, we came out of a narrow street onto a main

thoroughfare and found a canal in front of us. As we considered the best way

across, Sarah said suddenly, “Look. There is the University of Amsterdam.” What

do you know . . . a big sign on the buildings right in front of us, directly

across this canal. How did that happen?

We crossed the closest bridge and continued down side

streets into the University area, still not sure where we were. On one building

I noticed a plaque that read “Academic Offices”.

In that moment, the email from the director of the Menno

Simons Center surfaced in my mind. What was it . . . something about a

“Mennonite collection” at the University of Amsterdam, a curator I should try

to meet? No way—the chances are slim to none.

But, why not . . . what is to be lost by looking around? I fished around

in my wallet. Sure enough, crunched in a wad was my little note on the napkin.

I took the next right. Why? I don’t know. It was just there,

a long corridor with sort of a cloister look to it. I spotted a man putting books from boxes onto

a table. That looked promising. I stopped and asked him if he spoke English.

Politely he nodded his head. I asked him if he knew where the University

Library was. He said, “You are under it.” “You’re kidding. May I go in?” I

asked. He nodded again, “Check in at the desk, over there.”

We crossed the courtyard to the entrance of a newer looking

building. Surprise, there were people milling about everywhere—it is anything

but quiet around here. Inside the building, I discovered that, lo and behold, I

had walked into the international annual meeting of the Society for Biblical

Literature! Suddenly, I felt I was in familiar territory—I probably know some

of these people.

This was cool! I took a minute to wander about in the crowd,

hoping to see some of the SBL exhibits, maybe even a familiar face. Then, I

made my way to what looked like a guard station. I held up the half of a used

napkin and asked the guy if he knew where this was (my scrawl read, “Collection Mennonitica, Bijzondere

Collecties University of Am. Adriaan

Plak”)

Amazingly, he shook his head up and down. Then, he gave

directions to a branch of the library located a few blocks away (two canals

down, one across—really.) He said I might find someone there but he did not

know if I could get in.

The directions he gave took us back to the exact place we

had spotted earlier! We retraced our steps and found the address. The door was

unlocked—we cautiously stepped inside. (Will it be a dead end? Will anyone be

around? Will it be closed to non-students?)

Inside, there was another reception desk and a very nice

lady. Somewhat apologetically, I showed her my crumpled piece of napkin. She

said matter-of-factly, “Yes, that collection is upstairs. Go up there, leave

your backpacks in a locker, and then go through the double doors. You’ll find a

woman there who can help you.”

We go up the stairs, leave the backpacks, and walk through

some glass doors into a nicely appointed office area. At the main desk, a very

pleasant but smartly dressed lady with a confident, no-nonsense air looks up. I

must have been a sight: dressed in t-shirt and wrinkled pants, no appointment,

no idea what I am doing. I hope she speaks English. I hope she doesn’t throw me

out. She says, “May I help you?”

What else can I do? I hold forth my grimy scrap of paper and

point.

Without hesitation, as if on cue, she says, “Let me ring Mr.

Plak. He is in his office.”

Mr. Plak did not answer. (No surprise to me—no one is ever

around in the summer.) But she says, “I know he is there. Follow me. I’ll take

you to his office.” Oh, OK.

We walk down hallowed halls of ivy, through the rich

furnishings of an aged but undoubtedly storied building, past vast collections

of books and statues and serious academics in tweed jackets, gray beards and

reading glasses pouring over great tomes. We turn the corner into a suite of

offices. She approaches an open office door. This wonderful lady puts her head

in and speaks to someone in Dutch. A distinguished man gets up from his desk,

comes over, introduces himself: “Adriaan Plak. Please, won’t you come in?”

For the next hour and a half, Adriaan Plak and I talked

Mennonite history, theology, and the contemporary religious situation in

Holland and Europe. The ceiling of his spacious office is at least 14 feet

high—and every square inch is filled with books. As it turns out, the Collection Mennonitica is basically

right here in this room.

As we talked, I could not pull my eyes away from the

bookshelves. There they are: basically all the works by and about Zwingli,

Grebel, Manz, Hübmaier, Sattler, Riedemann, Marpeck, Simons—these men I have

been talking, reading, and thinking about and following across Europe this

entire month—all in one place. As my eyes sweep over the titles, I have this

surreal sense that they all came together here to greet me at the end of the

trip.

I have come to the Holy Grail (well, not exactly, but

close!) The story of the Anabaptists that started down in Zurich, wound its way

up through Germany and into Friesland and northern Holland (and eventually

throughout much of the world) is recorded and stored in the collection that

surrounds me here in this room.

What just happened? Why were all those people so quick to

help me get here? Why did this man happen to be available at this moment? Why

did he so generously give his time to a scruffy foreigner off the street?

Actually, I was so overwhelmed by this whole turn of events that it took me a

few minutes to collect my wits and engage in some semblance of a knowledgeable

discussion (and by that I mean put together enough words to sound half-way

coherent. Thank goodness they speak English.) It is a distinct possibility that

I just looked like a complete idiot and everyone simply took pity on me.

This has been a long story. But I had to tell it. How else

could this month have ended except right here . . . here, in the middle of the

biggest Anabaptist collection in the world, chatting with its curator, getting

a tour of the whole thing. He gave me his card and said, “If you have any

questions or need anything, email or call me.”

It was so fun, such a thrill, and not a little enlightening.

I will share more of our conversation in another post. By the way, I did not

take any pictures of the collection or the library—it might have been a bit

pedestrian on my part to do so but more to the point, I had left my camera in

the locker.

Oh yes, two other things.

First, in our conversation I remembered that one of the

questions I had hoped to answer on this journey concerns the English/Dutch

connection back in 1608-1611. Just how much did the European Anabaptists

(Menno’s followers) influence the English Baptists who came over with John

Smyth in that time frame and vice-versa?

Adriaan says, “That’s a good question. I’m not sure. There

is very little written on that. But perhaps we can find something.” He peruses

his catalogue and sure enough finds one book that may address this topic. He

rolls his 10-foot tall library ladder around to the stack behind his desk and

climbs way up, retrieving a little volume. He says, “Take a few minutes to see

if that is worth something.” As I flipped through it, he printed out the

catalogue information so that I could look for a copy back in the states. Are

you kidding me . . . . ?!

Second, that conversation led to him to ask if I was aware

of the “hidden Mennonite churches” in Amsterdam. This is a total surprise to

me. After I told him I had no idea, he says, “You should go see one.” I say,

“Where do I find one?” He says, “Why don’t I show you? We can walk there from

here.”

We went downstairs and found Karen and Sarah, who had been

in the library coffee shop all this time. The four of us, Karen, Sarah, Adriaan

Plak, and I stepped out into the bright Holland sunlight and strolled along the

canal to the nearest “hidden” Mennonite church.

No photos . . . just an amazing tale!

Tuesday, July 24, 2012

Amsterdam--Red Lights and Churches

Amsterdam—July 24, cont. Red Light District and churches

After leaving the “Our Lord in the Attic” church, we went

past the Old Church. This is the original city church, dating back to the

1300s. We will come back to it tomorrow, because closing time has already past.

We walked around the church a bit, just taking in the

interesting shapes and structural features of this medieval structure. One fact was impossible to miss: this old church is in the heart of the Red Light

District.

Amsterdam has taken a pragmatic approach to prostitution.

Street prostitution has been made illegal. In its stead, legal, licensed

(complete with tax number) prostitutes operate within the bounds of tiny

cubicles that line the narrow alleyways branching off the main street. Honestly, the sight of so many of these doors is an overwhelmingly sad and tragic sight. Enough said about that for now.

More to the point of this brief reflection: the presence of

this and at least five other churches in this part of town raises some

questions in my mind. I mean, some of the most obvious of the prostitutes’ cubicles

share the alley with the back of the Old Church. When you walk out the "back

door" of this ancient cathedral, you are looking into the doorway of half a

dozen of them. Barely 200 yards up the street is “Our Lord in the Attic”. St.

Nicholas’ and the four other Catholic churches that serve this parish, desiring as they

say “to provide pastoral and diaconal work . . . for the marginalized”, are

within blocks.

My questions? The churches have been here a long time. Did they slow

the incursion of prostitution and drugs into this area for any length of time? Did

they try? What did they see as their role? What was the reaction of the congregations to

the advent and eventual legalizing of these activities?

What impact did the culture exert on the churches? Did the

“world” finally “win” . . . did the churches simply cave to the inevitable? Did

they redefine their roles in the neighborhood? Will these churches eventually

cease to exist in this place, becoming interesting but lifeless museum pieces?

What is the role of these churches today? Are they in exactly

the right place, where depravity and debauchery are on full display, in order

to bring a safe, sanctifying, saving grace to the place . . . or should they

relocate (not an easy prospect in light of the giant cathedrals they have constructed)? Do they reach out to men and women who are desperate, lonely, and afraid

. . . or just hope these people will find their way in? Can these people even find a place in the church? Do the churches really make any significant

difference in this place? If so, what does that difference look like? What

should it look like? Is the world too strong, the brokenness so pervasive, that

the churches will likely never be able to turn this part (or for that matter,

any part) of the city back toward moral and spiritual well-being? Should they even

try?

I would ask the same questions of our church . . . or any

church, anywhere.

This is the "back door" of the Old Church. Across the alley, on the right, prostitutes occupy the cubicles day and night. I marveled at the casual ease with which families with kids wander these streets.

This is the view across the way from the front door of the church. What is not easy to see is the "coffee shop" behind the trees. At this coffee shop you can buy much more than a latte.

There are customers at these doors even in the afternoon.

Down a narrow alley, just off the main street. Proverbs 5:8 comes to mind (actually all of chapters 5, 6, and 7.)

Amsterdam--Haarlem, ten Boom house

Amsterdam—July 24 Haarlem, ten Boom house

We headed back to Haarlem (with walking, tram and train

rides, it is only about 45 minutes.) This time we went straight to the ten Boom

house. Naturally, the next tour in English was not for another 1½ hours, so we decided to go for another walk about Haarlem. We also found a wonderful little café with great

sandwiches for lunch. Then back to the ten Boom house.

Situated over the family-owned clock and watch shop in the

center of Haarlem, the ten Boom house was known in the area for being a place

of refuge. Casper ten Boom and his family were deeply faithful

Christ-followers. They demonstrated that faith in ready and generous service to

others. They were particularly active in doing social work in their

neighborhood. Their home was known as an “open house” for anyone in need—there were

always a few extra people living there—along with the parents, 4 siblings, and

3 elderly aunts.

Casper had many friends among the Jewish population. As the

persecution of Jews increased during the war, he knew he had no choice but to

offer them shelter. In doing so, of course, he put himself and his children

(the mother had died earlier) at risk of their lives—this non-violent

resistance against the Nazis was purely an act of faith in which he trusted

that God would somehow provide.

They smuggled bricks into the house and built a false wall

in Corrie’s bedroom, creating a space (entered through the bottom shelf of a

bookcase) where fugitives could hide if and when the police came. In time, they

sheltered Jews, students who refused to cooperate with the enemy, and members

of the Dutch underground resistance movement. The fugitives stayed until it was

“safe” to smuggle them elsewhere. The ten Boom house became a center of

underground activities that led to the saving of hundreds of lives.

In February, 1944, the family was betrayed, probably by

neighbors who observed all the activity in and out. The Gestapo raided the

house. In the following hours, the family and about 30 friends were arrested. (The six people who were

hiding behind the wall were not discovered. The police remained in the house

for several days, convinced there were Jews hiding there, planning to starve

them out. After 2 ½ days, the police left and the Resistance liberated the

six.)

Caspar and Corrie’s sister and brother died in the

concentration camps. Corrie survived Ravensbrück. For 32 years, she travelled

around the world, visiting 64 countries. She carried a message of love,

forgiveness, and the power of Christ who can overcome all, even the worst misery and

suffering. She wrote numerous books (“The Hiding Place”, perhaps one of her

best-known, is still being translated into other languages to this day.)

Her story is one of love for persecuted strangers as well as

for the persecutor. She lived out a faith that finds a way to forgive an enemy

who took everything away from her. This is a testimony of loyalty to the Jews

and of steady, resolute, yet non-violent resistance to evil. It is a story of

grace and obedience to the Lord.

We toured the house, preserved much as it was in 1944.

(Actually, the house is a museum, run by a non-profit foundation whose purpose

is to keep alive this spiritual heritage of the ten Boom family of Haarlem.)

The false wall has been opened up so that you may see the space behind it.

Documents, photos, and other mementos of that time tell the story in vivid

detail. The jewelry store downstairs rents the space from the foundation; the

rent helps with the maintenance of the museum.

This is a powerful and moving story. Once again, the theme

of non-violent, peaceful resistance arises. Once again, I ask myself the

questions: “Is my faith the kind that would stand in the face of death? Would I address evil with love? Would I forgive the worst kind of enemy?”

The ten Boom jewelry store on the street. The museum is to the left, down the narrow alley.

The plaque on the wall beside the door leading into the ten Boom house.

The hole in the wall allows you to see the very small hiding place.

I did not take too many other pictures in the house--it was kind of dim lighting and cramped space. I did not want to disturb the other visitors and don't think that too many of the photos, seen out of context, would make much sense anyway.

Amsterdam--"Our Lord in the Attic"

Amsterdam—July 24, cont. Our Lord in the Attic

We returned from Haarlem and Corrie ten Boom’s house. The

rest of the day was so interesting that I needed to make a separate post.

We decided to leave the train station and walk down the

street that goes to the Old Church in Amsterdam. There are several stories

here. First of all, the Old Church is the oldest of the city churches—perhaps

that is self-evident. Furthermore, we had to walk through the Red Light

District to get there—unavoidable: the church is in the middle of the District.

Before that, however, we came to one of the newer churches in the city, St. Nicholas' Church. This

one dominates the skyline as you step out of the central station. So we start there with the story.

St. Nicholas’ church is a beautiful, solemn church. It

opened in 1886. The Catholic Mass is celebrated in Monastic style, using both

Dutch plainchant and polyphony. Choral Vespers is sung on Sunday in Gregorian

chant. This church and the others that make up the city center parish are,

according to a pamphlet in the foyer, dedicated to being “a source of

inspiration for a living faith . . . (and) ensuring a broad scale of pastoral

and diaconal work is maintained in the city centre . . . for the rich and poor,

for faithful churchgoers and for the marginalized.” This is significant, a

worthy goal, in light of where the churches are located.

We proceeded from St. Nicholas’ down into the Red Light

District. The main street follows a canal—busy constantly with boatloads of

revelers. The street is lined with bars and seedy shops. It is very crowded

with not only young adults—students on holiday, 20-30-somethings who live in

the area—but older couples, families with kids, all kinds of people. This area

of town is a tourist attraction of the first order. I guess people see it

circled on the city map and just have to come see what it is all about.

Anyway, we are making our way through the throng and almost

by chance look up at a sign that is hanging over a door right on the street. It

says, “Our Lord in the Attic.” We had to stop and find out what this was about.

The most fascinating story was waiting.

In 1578, the Protestants took over the city. They not only

stripped the Catholic churches of their icons and altars, they also outlawed

Catholicism in the city. The Old Church (to which we are making our way) was Catholic

up to that time but was converted to Protestant by what is called “The Great

Alteration.”

Catholic churches were driven underground. By 1656, there

were 62 underground Catholic churches in the city. (Actually, by the mid-17th century, the

Protestants knew of their existence and tolerated these “papist meeting places” as long as they did not meet publicly, thereby reducing “the nuisance they caused.”)

In this particular instance, a Catholic businessman in 1663

bought three adjoining houses in this area and over the course of two years,

built a church inside. He cut through the floors to create the vaulted ceiling

of the church. He cut through the walls to make the chancel long enough to seat

about 150 worshippers. This clandestine church met for 200 years. The priest

lived in quarters inside the building, complete with kitchen facilities.

Freedom of religion came to The Netherlands in 1798. St.

Nicholas’ church was built a hundred years later. The Church in the Attic

became obsolete. The building was acquired and is being restored by a private

group to its original structure and colors. We had to take the tour. I hope the

photos do it justice.

Here is the fascinating thing: we were just in Haarlem,

thinking about Corrie ten Boom and a story of faith and persistence, of

non-violent resistance, of people who were willing to pay the price for their

convictions. We have spent the better part of the past month exploring the

stories and places of Anabaptists who were driven underground for their faith,

who were persecuted by Catholics and Protestants alike but who were committed

to live their faith, no matter what the price.

Now, we come to the flip side of persecution: the

Protestants drove the Catholic Church underground! These were simple people of

faith who wanted to worship according to their traditions and convictions. They

were seeking the same thing the Anabaptists sought. They were willing to go to

great lengths, to sacrifice safety and comfort. It wasn’t just the “radicals”

who were persecuted. Even though in many places the Catholic Church was the

persecutor and perpetrator of great suffering, here we find people of that

faith who were suffering in the same manner.

The issue is one of power. The group that is in control is

the group from which we have most to fear, regardless of their “good”

intentions. A power group always operates from a particular ideology, be it

socialist, fascist, or other. These groups pose threats to personal freedom and

responsibility. Equally dangerous is the power group that operates from a

religious ideology and motivation. Now "God" is brought into the mix and the group

justifies its actions as “God’s will”. This so easily leads to fanaticism and

extremism--and every other group is seen as an adversary, a competitor, and

possibly worthy of extermination.

We do not want to have any religious group, not even a

“Christian” group, in charge of the civil government—not Catholic, Protestant,

Evangelical, Islamic or anybody else.

We did not get to the Old Church today. We spent too much time in the Church in the Attic. We will come back tomorrow.

Set-back note: I left my little notebook in which I have been taking notes somewhere. I think I left it with The Lord in the Attic. I did get distracted by my conversation with the guy who was at the desk while I was retrieving my backpack from the storage locker. I didn't realize it was gone until we were well down the street. Fighting the growing Red Light District crowd, I hurried back up the street to retrieve it. But too late--by the time I got there, the church was closed. Oh well, perhaps we will have time tomorrow to come back and check to see if it is there. If not, I will just have to recreate the stories from memory. That could be a problem.

St. Nicholas' Church across from the Central Station.

Stained glass windows installed after WWII.

The altar of St. Nicholas' Church.

The organ in St. Nicholas.

A closer shot of the altar . . . pretty fance, huh?

The sign on the street in the Red Light District that caught our attention.

This is a sign inside the "secret Catholic church."

So, the builders of this clandestine church tried to get everything in that would make it a traditional Catholic church in which the worshipers would feel comfortable and at home. This is the font for holy water you encounter when you come up the darkened stairs from the street.

This is the worship center and altar. Notice that it goes up three stories. We are standing on the bottom level. There are two levels of balconies above. Note also that this bottom level is already two levels up from street level.

This is the altar complete with crucifix, altar paintings, and a statue of God at the top. The pinkish purple is the original color of the sanctuary.

We have a sacristy and vestments.

We have a Mary chapel.

This is another holy water font going down the back stairs.

The confessional which is in a back part of the house, above the street but below the sanctuary.

Yep, about all you need for a functioning Catholic church in an attic.

We did not get to the Old Church today. We spent too much time in the Church in the Attic. We will come back tomorrow.

Set-back note: I left my little notebook in which I have been taking notes somewhere. I think I left it with The Lord in the Attic. I did get distracted by my conversation with the guy who was at the desk while I was retrieving my backpack from the storage locker. I didn't realize it was gone until we were well down the street. Fighting the growing Red Light District crowd, I hurried back up the street to retrieve it. But too late--by the time I got there, the church was closed. Oh well, perhaps we will have time tomorrow to come back and check to see if it is there. If not, I will just have to recreate the stories from memory. That could be a problem.

St. Nicholas' Church across from the Central Station.

Stained glass windows installed after WWII.

The altar of St. Nicholas' Church.

The organ in St. Nicholas.

A closer shot of the altar . . . pretty fance, huh?

The sign on the street in the Red Light District that caught our attention.

This is a sign inside the "secret Catholic church."

So, the builders of this clandestine church tried to get everything in that would make it a traditional Catholic church in which the worshipers would feel comfortable and at home. This is the font for holy water you encounter when you come up the darkened stairs from the street.

This is the worship center and altar. Notice that it goes up three stories. We are standing on the bottom level. There are two levels of balconies above. Note also that this bottom level is already two levels up from street level.

This is the altar complete with crucifix, altar paintings, and a statue of God at the top. The pinkish purple is the original color of the sanctuary.

We have a sacristy and vestments.

We have a Mary chapel.

This is another holy water font going down the back stairs.

The confessional which is in a back part of the house, above the street but below the sanctuary.

Yep, about all you need for a functioning Catholic church in an attic.

Monday, July 23, 2012

Amsterdam--Haarlem (St. Bavo's), Rijks

Amsterdam—July 23

Today we decided to go to Haarlem (about 17 km outside

Amsterdam.) The main reason for going was to see Corrie ten Boom’s house.

You know the story: the ten Boom family harbored Jews,

members of the Dutch resistance, and others who were hiding from the Gestapo

during World War Two. But more of that tomorrow . . . . .

Much to our chagrin, we discovered the ten Boom museum is

not open on Monday! So, here we are in Haarlem with no other plan. What do you

do when your plan is interrupted? You just start walking, anticipating that

there is another plan in the making, an adventure waiting to happen, a surprise

around the corner. God always knows what is next and He simply invites us along for the journey.

We came to the massive Great Church of St. Bavo’s. Named for

its patron saint, St. Bavo (who knew?) who died in 653 AD. The old church has

existed in some form on this site since then. Construction on the present

church, following a fire in 1351, was begun in 1370. The rebuild required almost

200 years; the completion year was 1538.

Doesn’t it make you stop and think about church building

projects? A couple of years, 5 years—these seem like long stretches to us when

it comes to constructing a church building. Our emotional and physical (if not

spiritual) as well as financial reserves run out relatively quickly. It is

difficult for us impatient, driven moderns to wait; even harder for us to live

with a partly finished task.

We are generally quite concerned about our comfort and making sure our facilities are just right for us and our needs.

We are generally quite concerned about our comfort and making sure our facilities are just right for us and our needs.

What if it took us 200 years finally to finish our building?

Talk about building for those who are to come. The folks alive today, who are

making the plans, investing the time, putting up the money, will never get even

close to seeing the final product. In fact, their great, great grandchildren

may never see it. You gotta have some kind of vision, a huge, generous vision;

a faith that sees the big picture and looks into history—the history to come,

not the history behind—recognizing and affirming that God is about much more in

the world than you and your little piece of time yet also realizing that you

play a role in this stream of holy history.

Obviously, we know that our church is not the building

(although sometimes the place—the building—helps us quantify the entity). The

point is, we are always in the building process. We are always building a

church—for those who are here and even more so, for those who are to come. It

is incumbent upon us to have a huge, generous vision. We have to see the big

picture: this church is us, in our time and place, but it is also for many more

to come. And what about them? How much do we take them into consideration as we

“build” our church today? Our little piece of time matters in the history we

are making; i.e., this church we are building is not finished here.

So, the surprise for me today was the prompt from an ancient

church building; the thought that long building projects are symptomatic of the

more fundamental task of building a church that is forever. That makes me want

to stop and think some more about how we go about our business . . . .

Plus, there were some funny things that I observed that were most apropos!

Plus, there were some funny things that I observed that were most apropos!

We returned to Amsterdam with some daylight left (we are far

enough north that daylight lasts until 10:30 anyway), so we decided to go the

Rijksmuseum, the national museum. This monstrous place holds a vast collection

of memorabilia from the history of The Netherlands. It has displays regarding the

birth of the Republic through the uniting of seven provinces (two of which were

called Holland), the Republic as an international superpower (the Dutch once

had the largest navy in the world), a treasury of silver and goldsmith work, a

marvelous Delftware collection from the “Golden Age of The Netherlands”, and a

considerable collection of paintings from the Dutch Masters, including many

Rembrandts and his students and Vermeer and his Delft contemporaries. We stayed

in this museum until they ran us out.

OK . . . some pictures from around Haarlem. It is lovely, quaint; has canals; it is a little quieter than Amsterdam. We decided that if we worked in Amsterdam, we would live in Haarlem and commute.

The inside of the old train station.

The first canal you come to as you walk into town.

Same as all over Holland--lots of bicycles and people bustling about. This is mid-morning on Monday.

I was taken by this row of old houses, now apartments along a side street.

This building, on the town square, has the same style as those apartment buildings, set off by the pointed facade in front.

Looking across the town square from the church--it is a clear, warm day (there are apparently not may of these) and everyone is outside at a cafe.

St. Bavo's from the north.

St. Bavo's from the south west.

These little shops are built right into the side of the church, inside the buttresses that hold up the external walls of the church. They are clearly add-ons, not a part of the original structure. Somebody had the ingenious idea that these nooks were perfect for shops. They are now a permanent addition!

St. Bavo's from the south east. Now you can see why it took 200 years to build.

The Müller organ with 5068 pipes (the longest is 32 feet long.) In 1766, Mozart was 10 years old when he played here. G. F. Händel also played this organ.

The sign by the organ commemorating Mozart's appearance here in 1766.

Gotta love that pulpit, oldest part of which dates from around 1434. The bannisters are formed by two brass serpents, symbolizing evil fleeing from the world.

The choir is closed off from the front by a masterpiece of medieval craftsmanship, a brass screen from 1517.

This is the first church of this size we have seen with a wooden ceiling.

Way up in the corner of the ceiling is the date of its installation.

The chancel from the organ end of the building.

This is the first church we have encountered (there are others--this is just the first one we have seen) in which the entire floor consists entirely of grave stones. People with a little money and or notoriety could purchase a burial place in the church.

There are about 1500 gravestones in the floor altogether, the oldest of which date back as far as the fifteenth century.

The gravestone floor is polished to a sheen by the countless feet that have trod here. Walking on the graves of your forebears might be a powerful lesson concerning the passage of time and the importance of making your own life count.

To wit: a marker on a floor gravestone--skull and crossbones on top of an hourglass. Beware: you have only so much time and then you wind up here.

There are three model ships, beautiful craftsmanship, which were a gift to the church from the Shipbuilders guild, dating from somewhere in the 16th and 17th centuries. They are modeled on the ships that were built in Haarlem at the time.

In the back of the choir there stands a communion board. On its reverse side, seen here, is a report of the siege of Haarlem in 1573. Line 8 reports that the people were so hungry that "ja honden en catten waren wilbraet gheheten"; i.e., "dogs and cats were called roast game."

Every church, no matter where you are, has to have good coffee, gravestones or no gravestones.

This is the "Coffee Corner."Note: medieval surroundings; very contemporary espresso machine. Just sayin' . . . .

We don't have real problems. This is a cannonball in the wall, placed there as a reminder of the Spanish siege of Haarlem in 1573.

This means, basically, "Bread Bench." It tells the poor where to come to get their daily portion of bread.

This is the "Holy Spirit Bench" (also the "Bread Bench".) The Hold Spirit Masters handed out bread to the poor at this bench, which dates from 1470.

I had to take this series of pictures. This is the monitor of a closed circuit, live video feed that shows what is going on up in the organ loft. A concert is going to be taking place later today and the organists are preparing and practicing. (We actually got snippets of organ concerts in several cathedrals we visited--it is the season of organ recitals and concerts.)

You can see one of the organists sorting and stacking large pieces of sheet music (there was a sizable stack of these sheets and each sheet looked to be several pages taped together.)

He works and works to get the stack just right. He sorts and resorts until finally he is satisfied and then places the whole stack on the organ. Then he sits down.

The next musician comes up and immediately begins to resort the stack, apparently not satisfied the music is in the right order. I was mesmerized by this activity, going on in real time just above my head in the loft of an ancient cathedral in Haarlem, Holland. Apparently, it is the same all over the world: getting the right music, getting it in a usable format, taping multiple pages together thus having large, unwieldy sheets to manage, getting them in the right order, and then everyone agreeing.

This is encouraging, right?

A lovely canal just outside the church.

On the train back to Amsterdam, we tried to get a shot of one of the very few traditional windmills we saw anywhere in the country. The train was moving rapidly, there was reflection in the window, it was too fast to zoom in quickly--but I almost got it. Sarah got a better shot that I will share.

Delftware in the Rijksmuseum.

Cupid is telling everyone to hush as he (she, it?) carefully draws an arrow in order to shoot it into the heart of unsuspecting victim.

Sorry . . . I did not do very well in shooting Rembrandt in the museum. But I tried.

The famous Vermeer.

Rembrandt's famous "Night Watch."

This was cool. We watched how they move taller boats up and down the canal. Some bridges go up from the center.

Other bridges pivot on top of an offset pier, creating a passage wide enough for the largest tour boats. This was amazing engineering. The interface between bridge and street was almost invisible due to the very close tolerance in the curved joint.

The big boat goes through . . . .

The little guy sneaks in after it . . . .

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)