Amsterdam—July 25, cont. The Hidden Mennonite Church

So, Adriaan Plak walks us to the “hidden church.” We go

across the canal and west a little ways from the University Library. We

approach a door that is plain . . . it does not stand out from any other door

on this street-front building. In fact, that is why it is called a “hidden

church”—meaning it is not recognizable from the street.

We walk inside and can see immediately that we are in a

large facility with a very church-like feel. (There is the secretary’s office,

the coffee machine, and stacks of bulletins, brochures, and other church

paraphernalia.) We walk around to the sanctuary. It is pretty plain: dark

wooden floors and pulpit, large balcony with painted posts and railings. A very

interesting art piece is on the pulpit. You’ll see a picture of it. There are a

couple of nice chandeliers—the only decorative pieces.

The center of the sanctuary has folding chairs. In the old

days they were stacked in the foyer before the service began. Each female churchgoer

took a chair after paying a five-cent piece and carried it somewhere into the

middle area. The surrounding benches were intended for the men. The children

from the orphanage that the church operated and paupers usually sat in the

gallery.

In walked a slight, younger middle-aged guy who introduces

himself as Marcel Alblas. Adriaan excuses himself and Marcel takes over. He is

engaging, obviously loves to talk (and talk about his church--he is the

facility manager and guest host) and has a wonderful if understated sense of

humor.

Marcel says he grew up in the “Bible Belt”—the one in

Holland— which means it was “Reformed” (his words.) It was very conservative:

no cinema or swimming on Sundays. That strictness was too much for his family

and pushed them toward a more liberal outlook.

He is definitely what you might call a “liberal” (you might pick up on

that in some of what he said; see below)

He took us on a tour of the church and unloaded more about

the history and practices of Mennonites in Amsterdam than we could possibly

absorb. (I took notes as fast as I could.) It was an enjoyable conversation and

fascinating. Once again, it was almost too much to believe—discovering this

church, being here and hearing all of this was nowhere near my mind a few short

hours ago.

Here is short summary of his comments:

In the earliest days, from 1530, during the times of

persecution and weirdness (he mentioned the “naked

truthers”), Mennonites met

in private homes. At the beginning of the 17th century, when the

Protestants began to tolerate the Mennonites to a certain degree, they began to

meet more often in central gathering places. Still, they did not publicize to a

great degree the locations of these places.

The Mennonites were allowed to have a meeting place but they

could not be visible from the street, could have no clock tower, and no church

name. Marcel commented that the city fathers managed the churches like they

managed the drugs and prostitution: tolerate them but know where they are so

you can keep an eye on them (thus the “coffee shops”, the Red Light

District—and hidden but registered churches.)

In 1607, the first building was built on this site. This

meeting place was called “Near the Lamb.” One might think this was a use of the

biblical reference to Christ the Lamb. Actually it referred to a lamb on the

gable of the nearby brewery. The lamb is still the church’s logo.

In 1639, a larger structure was built on and in 1839, the

roof took its present shape. Over the years, the complex continued to grow. It

was used for meetings, a library, and Bible classes. This is a large facility.

It is the headquarters of the General Mennonite Society and the Mennonite

Centre for Congregational Building. Marcel refers to it as “the Vatican of

Mennonites.”

A library was founded in 1680 with a pastor’s small

collection, to be used for the benefit of preachers. This collection expanded

throughout the 18th and 19th centuries through many

endowments and has grown into a collection of books by and about Mennonites unequalled

in the world. Guess where it is . . . it is “on loan” to the University of

Amsterdam across the canal.

There is another library used by the Mennonite Seminary

(which uses space in this church also). This library contains literature in the

field of church history, doctrine, biblical studies, and ethics.

He showed us a large multi-purpose room. This is where the

Church Board meets. This is also the room where they feed the homeless on

Friday nights. It is also the room where they welcomed the Queen a couple of

years ago.

“Mennonites have a strong belief in strict separation of

church and state,” he said. “We have a hard time voting for so-called

‘Christian political parties.’ They sometimes take hard stands on issues they

claim are ‘Christian’ but these are positions with which you or I or some other

Christian may not agree. Sometimes they do not act like Christians at all. Best

leave politics to politicians and faith to believers and the church. We can

sort things out.”

“The Netherlands is not a Christian nation but it has

Christian values. That is why the state

takes care of the elderly and homeless. That is also why we do not send our

children to the state-funded religious schools but to the public schools,

instead.”

The pastor is not called “pastor”. He is called a “teacher”

(leeraren)—which is what his role is

in the church body. The pastor is just one person in the congregation—he is not

“higher” than anyone else. Actually the congregation is the ruling body. The

pastor gets one hour a week. At the beginning of the worship service, the

president of the congregation shakes his hand and introduces him. At the end of

the hour, the president comes up, shakes his hand and sends him back to his

seat.

During Reformation time, this was the biggest church in

Amsterdam, Marcel said. Today, it is the smallest. It has consistently grown

smaller. I asked him the same question I asked Adriaan: “Will this church be

here in a hundred years?” “Of course it will,” he replied. “Because the spirit

is still alive in people who seek truth and who wish to be free. We don’t have

all the truth but we are near it. We are always seeking it.”

Mennonites believe strongly that faith is demonstrated in

deeds. For Marcel (and apparently this church), that means several things. It

means they feed the poor and have children’s ministries. They are also

gay-friendly—open and accepting. Next month they will host a gay wedding. (This

is actually not a big issue in Amsterdam, as you may know. Homosexuality is

very public and openly accepted. Amsterdam Gay Pride is socially and

politically active. The “Gay Monument” is not far from this church. The big,

pink, balloon barge is hard to miss in the annual Canal Parade. I saw a picture

. . . .)

They believe that every person is responsible for “writing

his own creed.” That is, each person defines his own understanding of and

experience with God and is responsible for how he expresses that faith. “We

don’t dictate how others should believe. People are not expected to check their

mind at the door (for example, evolution is not even an issue; science and

religion walk hand in hand),” he said.

“Attendance is not expected every Sunday of every church

member. It is just as important that members live the faith. They should

occasionally use a Sunday to do some kind of service. Then they come to church

to be recharged.”

This church sponsors a public forum on social issues each

month. They bring in speakers from the community who speak and lead discussions

on a wide range of topics. Apparently this has become quite a popular event.

Other churches around Holland are copying the model. Marcel was very proud that

one of the speakers coming soon is an outspoken atheist who will lead a

discussion on why she rejects faith in God altogether. The name of this event

is called in Dutch, “Dopers Café.” It roughly translates “The Baptist Café” but

its English appearance has a different connotation.

Mennonites may be progressive here in the big city but they

have not forgotten from whence they came. Marcel brought out a big,

leather-bound book, a quite old one by the looks of it. We could not find a

publication date in it. He said they put this book on the altar every Sunday

morning. When he first saw it, he was put off. “What is this?” he asked. “Are

they worshiping this book instead of God?” Then he learned why the book is made

public on a regular basis. It is put out every week to remind the people of

their heritage and of the people who’s faith cost them their lives. It is an

antique copy of The Martyr’s Mirror.

So, we have now seen the spectrum—there are very

conservative Mennonites with the traditional dress and lifestyle; the more

“moderate” (as we met in Langnau); and today we meet the urban liberal. Each

church has adapted its faith and practice to its surroundings. Somehow, though

I think he would respect his Dutch brother, Hans Jützi down in the Emmental

might not agree with some of the social positions and biblical interpretations

of Marcel Alblas up in Amsterdam. Marcel might think that the country version

of Mennonites is a bit restrained—but he would insist that every believer must

“write his own creed.”

Here is the illustration of the fact that the movement

grounded in “evangelical humanism”, rigorous biblical study, and insistence on

freedom to live one’s faith as conscience dictates and the Spirit leads is

capable of manifesting itself in a stark array of disparate expressions.

Oh yes, one other thing: when I mentioned to Marcel that I

was from the “Baptist” tradition in the United States, he said, “Oh, you are

part of the English!” I wasn’t sure just what he meant. He led us to a large

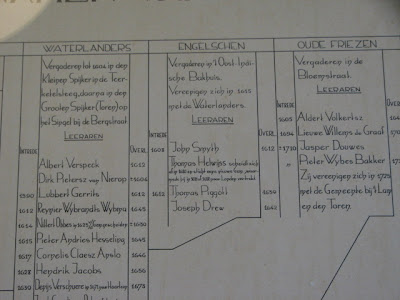

display on the long entrance wall and showed us a schematic description that

portrayed the history of this Amsterdam Anabaptist congregation. Refugees from

across Europe had come together in this church. There were Flemish, Frisian,

other European groups . . . and an English group. The names of all the deacons

and preachers (“teachers”) of the congregation from the very beginning up to

present were there.

And there, right

there in the middle of the display, up at the top, under the column heading

“English”, dated 1608, was the name: “John Smyth.”

So, this is the place. This is the place for which I have

been looking. This is where those English “Baptists” and those Dutch Mennonites

came together, worshiped, studied, discussed, argued and prayed. It was from

here that the little English group eventually went back to England and then to

the New World, taking with them some portion of the legacy of faithful European

Anabaptists.

I guess I got my answer . . . today . . . the last day of

the journey.

Oh, yes. After this amazing day, we finally made it to the Old Church. There are some photos below.

And, I dropped by "Our Lord in the Attic". They had my notebook.

Oh, yes. After this amazing day, we finally made it to the Old Church. There are some photos below.

And, I dropped by "Our Lord in the Attic". They had my notebook.

Walking along the canal towards the "hidden" church. Actually, you would never know there is a quite large church facility behind the black door with the arched top, in the center of the picture. The Catholic Church next door is much more obvious!

The front door of the "hidden" church.

This is the sign that hangs over the door. "Mennonite Community" (or "Fellowship")

The Lamb symbol is taken from the "Lamb Brewery"which was nearby.

A metal plaque on the exterior wall above the door shows a lamb (to symbolize this church) and a sun and a tower which are the symbols of two nearby "hidden" churches. The plaque reveals that they knew about and cooperated with each other.

“A book lies open on the pulpit. Pages flutter as if playfully caught up by the wind to be suspended frozen in the air.” This is the poetic description of a sculpture by a local artist on exhibit this summer in the church. The sculpture is done in alabaster.

Marcel gently holds the church's old copy of The Martyr's Mirror.

The wall display which shows the history of this church. It names all the deacons and pastors (teachers) who have served in this church from its beginning. Each column represents Mennonites from various regions who came together.

In the middle of the display is the "English" column. Two very familiar names, John Smyth and Thomas Helwys, are right at the top. Note that they are listed as "leeraren" or teachers of the church in 1608.

This sign beside the door next to the church door indicates this is the meeting place for the Mennonite Seminary and the General Mennonite Society.

After we left the hidden church, we walked down to the Old Church. Here are a few photos.

A brief history of the Old Church in Amsterdam.

Note the rather dismal tone, both in terms of how the Protestants treated the formerly Catholic cathedral as well as how the "new church" eventually replaced.

A confessional booth in the Old Church. This would have made a perfect wardrobe for a C. S. Lewis play.

The Old Church has a floor of grave stones and a wooden ceiling.

The organ of the Old Church. It is interesting to note that these very nice appointments are maintained in a church that is rarely used a church anymore.

This is the grave of Rembrandt's wife.

Every church has a first song and a last song in its worship service. These hymn boards were in every church we have seen.

The dark, somber pulpit has a highly polished brass railing.

When we build a balcony or a loft for our sound booth, we can use a spiral staircase like this one.